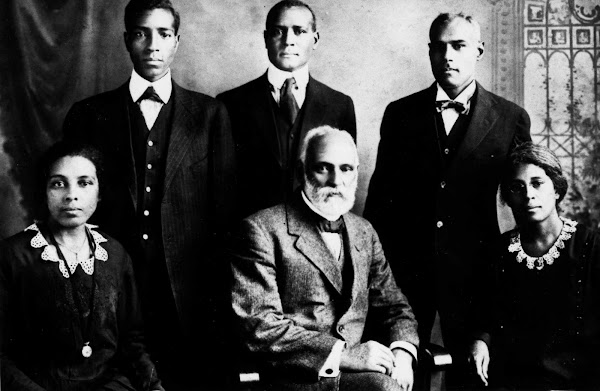

Uncle Teddy was thirty-eight years old and had never been married, but soon he would take a wife. In his last year of bachelorhood, he spent as much time as possible traveling around the country -- painting, trying to drum up new commissions, visiting family and friends, and attending conferences. In June of 1920, still president of the Charleston branch of the NAACP, he was in Atlanta for the organization's regional conference, where he witnessed a historic event: his mentor DuBois received the organization's highest honor that year.

Atlanta, June 2, '20

My Sweetie,

I did come to Atlanta though at the time of the receipt of your card I was by no means sure if I could make it. Many of our folks urged that I come to the conference. It is a fine gathering quite worthy of the cause, and I have been very much inspired by hearing the finer things said here in the heart of the Cracker country.

Have met many old friends and acquaintances of other days, among them the darling Chrystal Bird.

There has been time to do nothing but attend the three sessions a day closing at midnight, but I may remain over a few days.

I have been anxious to have a word from you but as I expect so soon to return I shall have a hatful of anticipation until I get home. Shall write you again before I get back.

Dr. DuBois was awarded the Spingarn Medal yesterday at a most beautiful ceremony on the campus of Atlanta Univ.

Oh say! Have wished that this could have been my honeymoon trip but it has been impossible. However it will not be afar – if you say so.

With love and best wishes with a kiss and another and another ad infinitum ...

Affectionately,

Teddy

Elise's response to Teddy's June 2 letter is missing, along with any others she might have written while he was away from home. In this one, whose envelope bore the date June 29, 1920, she gently scolds him for his lack of communication and gives him instructions on how to prepare for their new life together.

Dearest and bestest,

Having waited what seems months to hear from you, I feel it my Christian duty to remind you that I love you just the same and that I would be very happy to have a "few lines hoping I'm well" and saying you love me still.

Long dreary days of silence make me wonder just what kind of love you have for me. I'm beginning to think it is "tainted," that it is not "all wool, yard wide, dyed in the yarn" kind. Will you say aught to the contrary?

Of course I've heard you have been travelling around the country and I know they don't sell stamps nor issue telegrams in those little by-ways where the trains carried you, so I forgive you for not writing me the past months altho you did say you'd write me before you left Atlanta. So in order to get into my good graces again, you'll have to go back to Atlanta and write -- see?

Or else -- sit right down now this very minute and write me.

I suppose you've been selecting the dumb witnesses of our future happiness and if you have made me a white kitchen, a dark cool looking dining & living room and a delightful bedroom somewhat on the order of [your sister] Eloise (don't forget the vanity table), why I'm ready to come to or rather with you whenever you say -- but please say -- write -- write if you only say you're thinking of doing something.

Don't forget the pots and pans and groceries and tea wagon and can opener and ice pick and vacuum cleaner and electric coffee percolater. Have the telephone extension made to top floor and the little table beside the bed for the telephone and electric floor lamp. ...

Although she had been away from home for months and was eager to settle down, Tantie received a letter from Teddy hinting of his desire for her to continue her studies at Tuskegee Institute under Cornelius M. Battey, "the dean of black photographers." Battey's most famous student was the legendary P.H. Polk.

121

June 30, 1920

Sweetheart,

Your gentle letter was awaiting my arrival from the “provinces” and your card no. 1 with its reminder. Then came your other card – no. 2 with its little Threat and a’ that. ...

Why didn’t you ask me something of my trip? You surely are interested in my wanderings. Let me tell you of one incident: I went to Tuskegee. I wanted to see a few people and a few things there – Halsey, my classmate, who runs things in a measure; his wife, one of our crew at A.U. and another gentleman whom I hope you will soon know, Mr. Battey, the real photographer – the artist par excellence in his line, head of the budding school of photography there.

I want you to get some of his amazing skill, and have already written him about you. I think he may be in your city soon and if he does you can talk shop with him.

Perhaps next summer, if you care to do so, you can work with him at Tuskegee in their wonderful new building, a part of which is designed especially for his work. He is not very enthusiastic over your school, but one could hardly expect one of his calibre to be so – he is one of the “cracks” of the world.

Perhaps you will tolerate my mentioning this at length because it may have a definite bearing upon our “business.”

You see, it’s a bad thing to be poor [when planning a wedding], for this is a time when the erstwhile “comfortable” and even the “well-to-do” people must be considered as poor, and we are surely in that category.

Now, suppose you come home. Could we very well do without a “church and reception” wedding? Would you be prepared to fashion a sure-enough trousseau? I went to the Ransier-Gaillard reception downstairs and it was merely a pleasant dance given by Tom. The Dawson LeRoach affair was shoddy.

Or would you prefer to have me come for you in New York, take a trip eastward and then return to the Sunny South?

I confess I have forever dreaded the idea of the ordeal of a public wedding with its stiffness and pomp relieved by the coarse jests of certain “friends” who would be funny; but on the other hand I have so admired a bride that never have I dared to hope to be worthy of anything so ethereal and have always wondered that the average bridegroom should dare to presume to call something so beautiful and holy “his own.” But nothing is to be denied a bride, Lise, and I will do as you want me to do with you, for you and, so far as I am able, by you. ...

It would be a source of great relief to me to be able to get the valued assisting suggestions or even direction from Marie and Eloise, but the [former] is still sick abed and the latter has gone to Hampton to summer school. But we shall do the best we can by all means. ...

I can’t go back to Atlanta to write you, for I have bid goodbye to all my folks there as a bach and had benedictions said for my bride. You see, I’ve never had one before and I don’t know how to act, so I will henceforth be very docile and take lessons from you, knowing me. First of all, I presume, is the matter of writing and as there is much to be said I’ll write often. ...

Everybody has chided me for not writing often and I have not changed much. That’s one of the reasons why I have repeatedly offered myself to you as I am. You already know me, and I am inclined to be honest, so when I have repeatedly protested my love and offered it – all of it -- I have meant it and still mean it. It may be a poor sort of love not to make a lot of fuss and frills but it is genuine and it will not change, except to grow. ...

Goodbye for today with all my love.

Forever yours,

Teddy

Meet Theo Lockrow: 2025 Vibrant Leader Intern

6 months ago

No comments:

Post a Comment